- This is Big

- Posts

- How Mitchell Elegbe Built Nigeria's First Fintech Unicorn 🦄

How Mitchell Elegbe Built Nigeria's First Fintech Unicorn 🦄

Mitchell's Five Cardinal Principles.

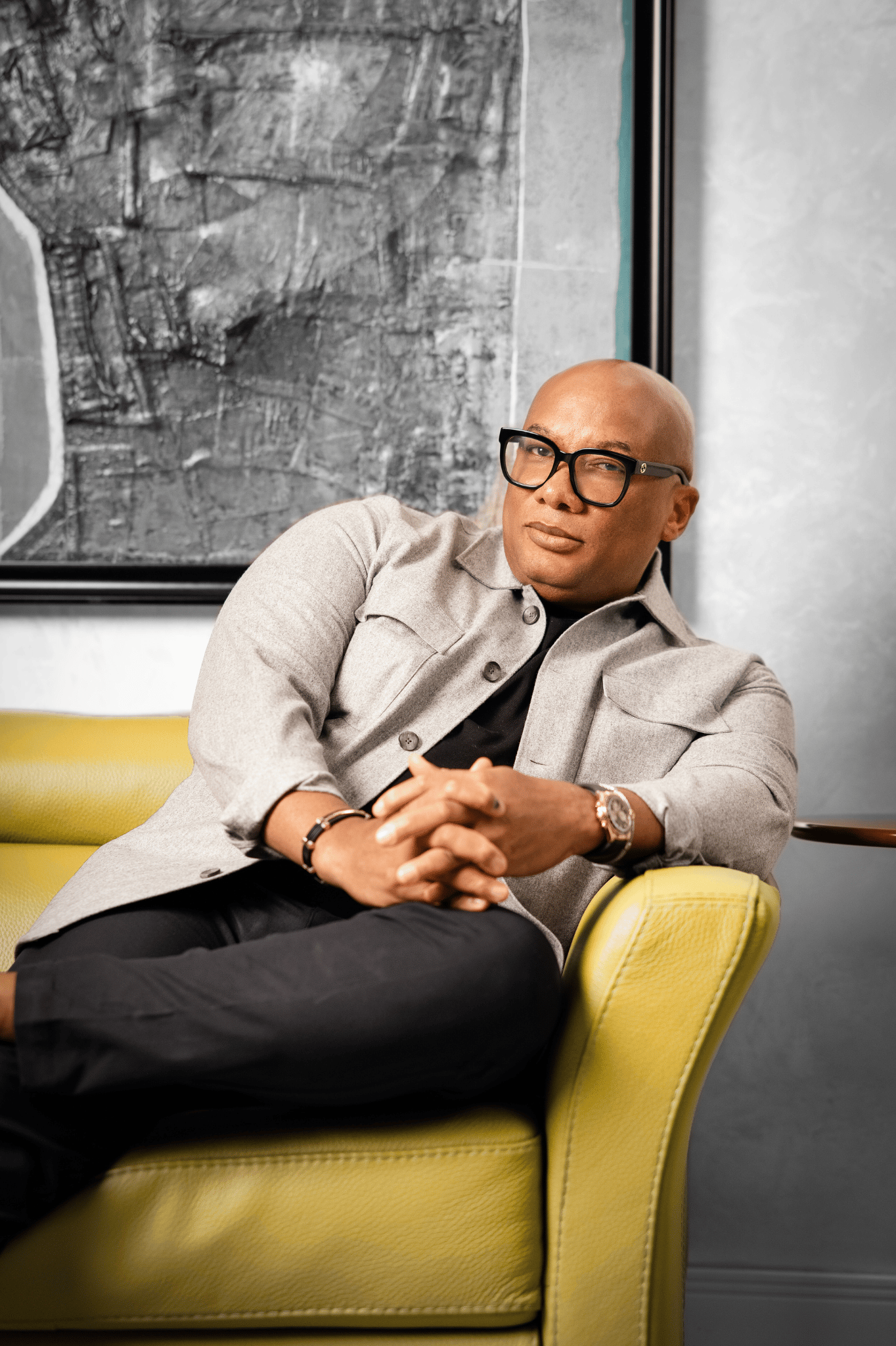

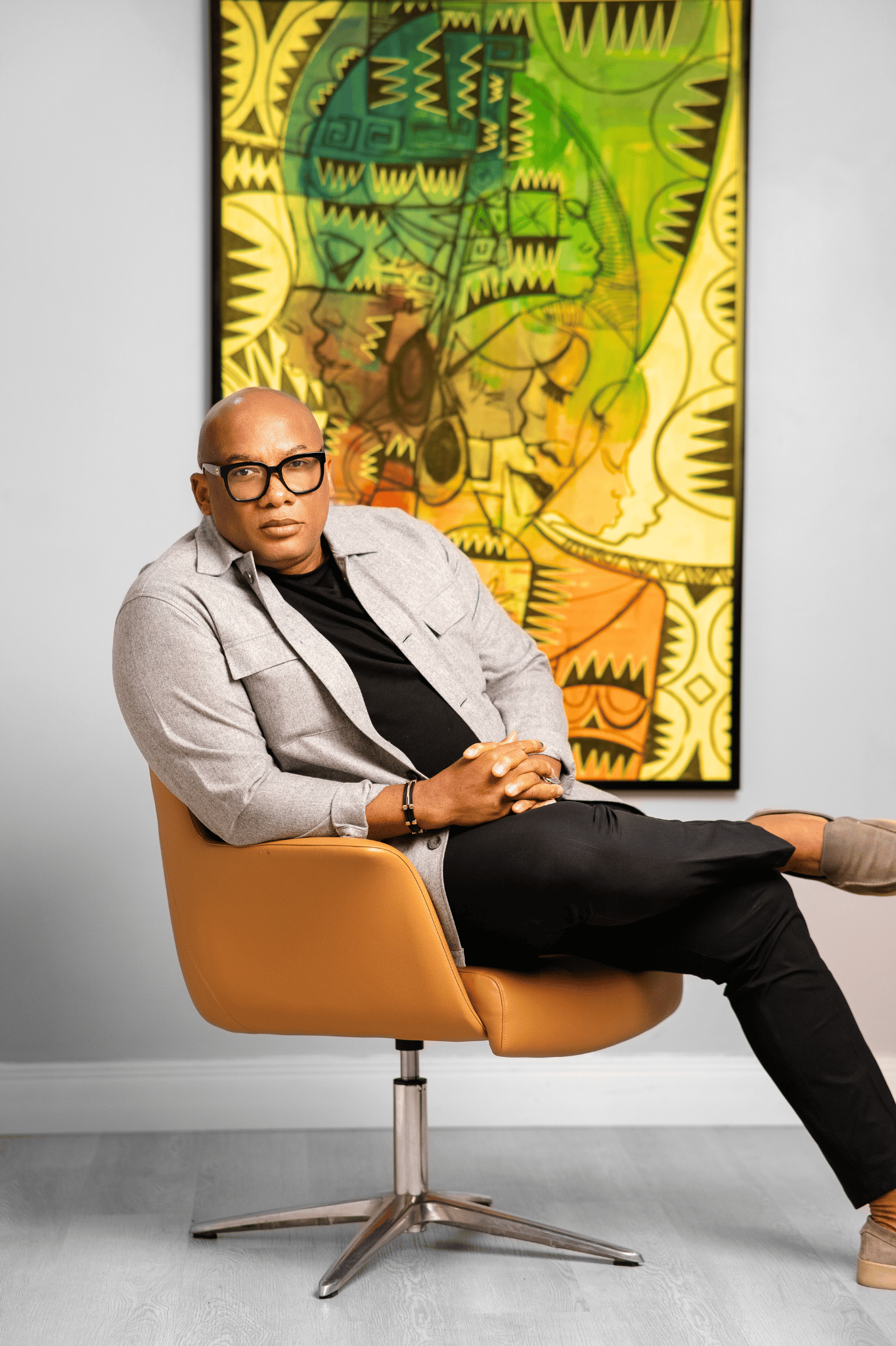

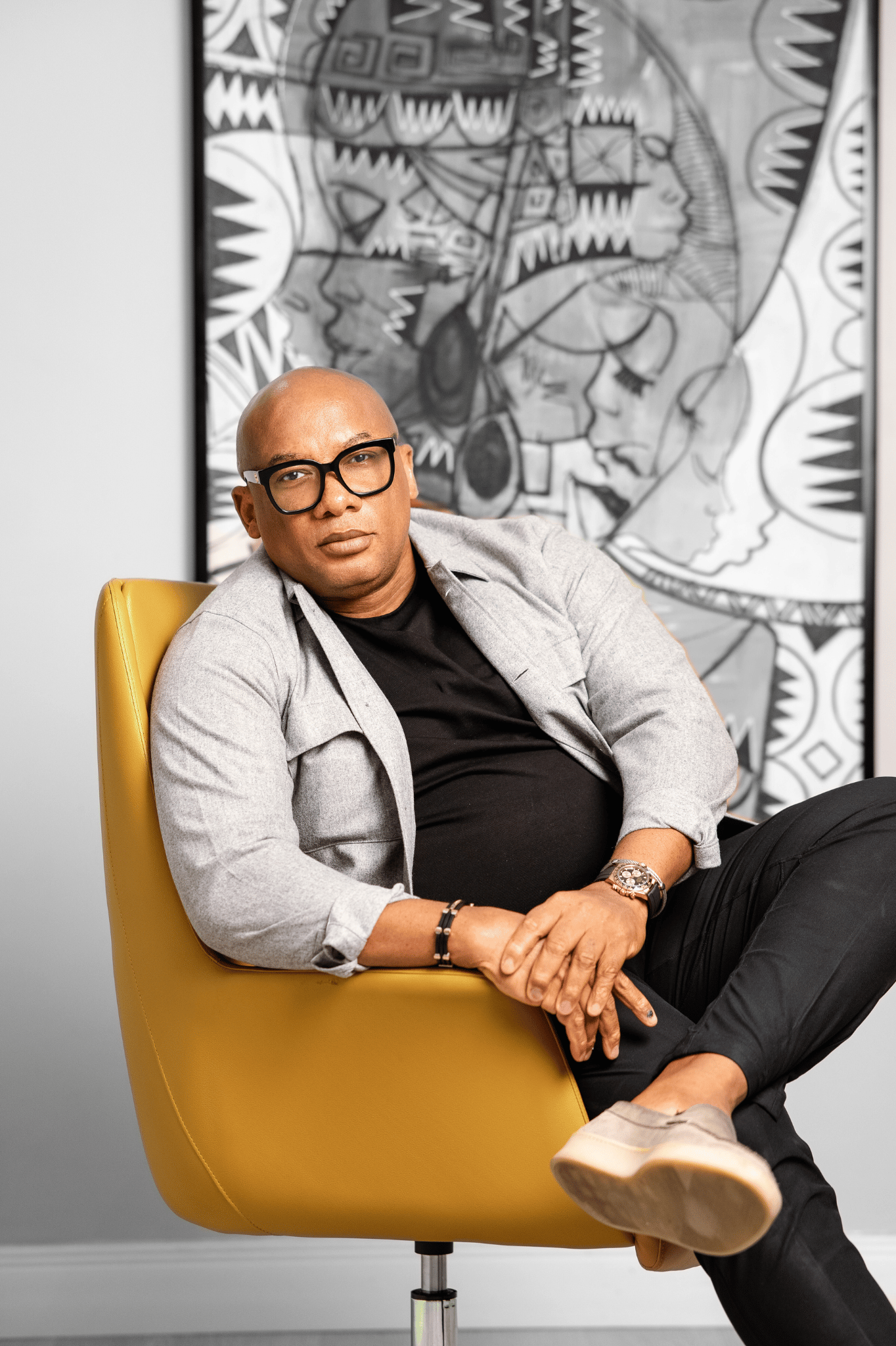

CEO, Mitchell Elegbe. Image Credit: Interswitch.

Mitchell Elegbe is gearing up for Act II.

It’s a Monday afternoon in Lagos, and the air, for lack of a more poetic description, feels like the vocal stylings of Glorilla’s TGIF song, 95 degrees and humid. It’s the kind of Lagos energy that promises both opportunity and an imminent, sticky sheen of sweat.

After two decades of building Nigeria’s first Fintech unicorn, Interswitch, Mitchell, now in his early 50s, is fired up for his second act at the helm of the company that’s defined his adulthood.

We are not a payments company, we are a technology company. And if you look at it from this lens, we still haven’t scratched the surface.

When my cab dropped me off on the bustling Oko Awo Street, an essential part of Interswitch’s DNA – similar to Menlo Park’s significance to Meta, a security guard proudly declared, “This street na Interswitch street”, as I asked for Building 1. |  |

Nigeria’s first fintech unicorn has, for over two decades, established nine buildings on Oko Awo, with employees walking the street for meetings in sister buildings or to get their steps in. Building 1, where I meet CEO Mitchell Elegbe, is Interswitch’s first office and HQ, and the one Mitchell has a fondness for.

Mitchell walks into the room with the calm energy of someone who has already seen the end of the movie and quietly accepted the plot twist. There’s no performance, just reflections and a deep philosophical belief in employee spousal stipends.

Yes, spousal stipends!

Interswitch pays out quarterly stipends to the spouses of its staff — a quiet tax for their sacrifice. “If your spouse works at Interswitch, we’re going to pull a lot of their time”. Mitchell explains, with the kind of straightforward logic that makes you wonder why every big company on the planet isn’t doing this. “This is our way of saying to the spouses that we understand the sacrifices they make.”

It’s the kind of detail that’s often missing from established companies, where employee benefits are not directly carved out for spouses, but it’s at the heart of everything Mitchell values about his company: the people.

That same value extends to sharing hard-fought lessons with young African founders by showing them the ropes before it’s too late.

His critique is sharp and unflinching.

“You don’t have to know what to do,” he says. “But you must know what not to do. Otherwise, the thing will kill you.”

It’s fascinating to hear his observations of an industry he helped build. When he was coming up, he sought out people building great companies for help or advice when he needed guidance, but admits it’s different now.

“I started Interswitch at 29 years old, three years after my national service. I was very young. “I didn’t expect to be CEO,” he admits, with a slight chuckle. “But I knew Interswitch was a company that had to exist. I didn’t seek out mentors, but they were people I respected and turned to when I was unsure, even for something as simple as drafting a bank letter. I called my old boss for that. I wasn’t ashamed. After a few weeks of going to him, I didn’t have to anymore, because I got confident in what I’d learned,” Mitchell says, “but people don’t do that anymore – till they get in trouble.”

So, I asked him about the advice he’d give his son to guide his entrepreneurial journey, if he asked him, “Dad, how do I build a unicorn?”.

The Five Cardinal Principles

He hasn’t written them down, “maybe I should,” he laughs — but they’re etched deep in his mental framework. Mitchell calls them cardinal principles, but they could easily double as survival rules for anyone trying to build something in a market that often behaves like it’s actively resisting progress.

#1 - Know the Problem You’re Solving, and Why It Still Exists.

This, he insists, is not a buzzword. It’s not a bullet point for your pitch deck. It is not, he stresses, a vague nod to “financial inclusion.” It should be a clear reality that plagues your market, a tangible pain point that keeps people awake at night.

If you can’t distill it into a single, declarative sentence, you are, by Mitchell’s reckoning, simply not ready. “You must assume many people are trying to solve the same thing,” he says, “So the problem has to be big enough — and your answer has to be different.” There’s a certain elegance to this brutal simplicity.

#2 - Have a Business Model—a Real One.

His second principle is blunt: no matter how noble your mission or sleek your app, if your economics don’t work at the price your customers can afford, you’re building a mirage.

You can’t raise money on a beautiful story. You need a model. And that model doesn’t have to be obvious to anyone else, but it must be crystal clear to you.

At Interswitch, he calls it a delivery strategy. They partner with competitors. They train future rivals. Their “secret” is hiding in plain sight, but only if you’re looking at the infrastructure.

#3 - Context is Not Optional.

Mitchell calls it the Tropical Savannah Principle. What works in California will not necessarily work in Calabar. Mitchell is not anti-globalisation, he’s just sceptical of cut-and-paste ambitions.

“Problems are local. The solutions must be too,” he says. “Even if you borrow international best practices, they need to be domesticated.”

And yet, his outlook is not provincial. It’s continental. Interswitch was profitable by its second year, not because it avoided ambition, but because it refused to ignore the math of its biggest market.

If you try to scale like a Silicon Valley company here,” he warns, “you’ll burn through cash trying to convert customers who were never going to pay.

#4 - Get Your People Strategy Right.

Mitchell morphs into the man who has seen good people burn out, break down, and quietly disappear.

“You must love your people,” he says, not as a management philosophy, but as a biological fact. “And they must feel that it’s real.”

In addition to spousal stipends, the company covers medical expenses for treatments that exceed HMO limits, as well as extended work-from-home programs for employees with families abroad.

The company has built an infrastructure for human beings. “You cannot fake love for long,” he tells me. “They will know.”

#5 - Your Economics Must Match Your Environment.

“Africa is full of poor people,” he says. “Brilliant, capable people — but poor. If your business model doesn’t account for that, then what exactly are you doing?”

He says it without hesitation, not as a judgment, but as a diagnosis.

If you’re copying a Silicon Valley model that burns cash for five years while waiting for your users to become wealthy, you’re not building a business. You’re gambling.

This is his most radical principle, and also his most obvious – your customers cannot sustain a pricing model that assumes they’ll someday become middle class. They were never yours to begin with.

“The minute you try to monetise, they disappear,” he says. “Not because they’re disloyal, but because they never had the means.”

Act II: The Fundamentals of Living.

Mitchell lights up when he starts talking about healthcare becoming Interswitch’s next act. It’s a curious pivot for a company that has spent two decades in payments, but he sees things differently.

Payments was never the end goal. It was the beginning. What we’re doing is building systems.

He views healthcare as a vital part of living a full life.

“Healthcare is another fundamental of living. If you get payments right, you unlock transactions. If you get health right, you unlock people.”

He’s not interested in “healthtech” as a disruptive opportunity, but rather in systems that make care possible — data that travels, access that works, and institutions that communicate with each other. It’s less about disruption, more about repair.

“We don’t lack smart doctors, we lack the infrastructure to let them be excellent. You focus on the fundamentals,” he says again, as if reminding himself about the things that help people live decent lives – and then you build from there.”

Big Mitch & IPOs.

I asked a more personal question. “Why do people call you Big Mitch?” He laughed. “It is the African thing. Here we go by first names. And when I employ people, they find it hard to call me Mitch.” So “Big Mitch” was a compromise. “Those that cannot call me sir, call me that. Then I started feeling big myself to reinforce it.”

The inevitable IPO question. Interswitch had signalled a London listing back in 2019, but it never happened. Many assumed it was cold feet, given the pressure other African fintechs face to go public.

He didn’t flinch. “When we did the Visa deal, we became a unicorn. I thought it was a more marketable deal than going public at the time. So the plan was to go for that deal. And then we go public.”

The market, he explained, disappeared after the Visa deal. “It was a good thing we didn’t go public.” He mentioned “issues with the Naira” and other factors. “I’ll do what’s best for the company and what is best for shareholders, but an IPO is not completely off the table.”

Wellness is a Must.

Building a company for two decades requires some level of mental and physical acuity. Mitchell doesn’t say this outright, but it becomes evident in the way he discusses recovery, renewal, and the quiet disciplines he has adopted along the way.

He wakes up at 6:30 every morning. Spends time in the gym at home. Walks. Lifts. Thinks.

“I like to spend time in the shower,” he tells me, not self-consciously. “It’s where I clear my head.”

Saturdays are for long walks, sometimes two hours, and brunch. No breakfast, no schedule, just movement. Sundays are slower—family, church, rest.

One of his biggest regrets was not learning how to swim, but it’s still a goal. Instead, he spends time by his gorgeous “pool with a view,” where he rests or reads books. The goal is not to burn out. Just routine. Intention. Space.

You have to design your life like you design a system,” he says, somewhere between a reflection and a closing line. “If it breaks, everything else breaks too.

If Mitchell Elegbe could rewind time to his 29-year-old self that stood in front of an ATM in Scotland, with a bright idea to launch Interswitch, Nigeria’s first unicorn – would he tell him to run from that idea or dive headfirst?

“Dive head first. I would have been more bullish,” he says, in a rare display of grace to his younger self. “But I’d have had the opportunity to move faster, trust my gut, not hold back.” That younger Mitch, he admits, was “very cautious”.

The 29-year-old Mitchell, one imagines, would covet the five cardinal principles his 2025 self has painstakingly collected over 23 years of running his company. With them, he’d have been swifter, more decisive. “Everything I’ve accomplished,” Mitchell Elegbe confesses, “could have taken me ten years, instead of the length of time it took.”

Here’s to Act II.